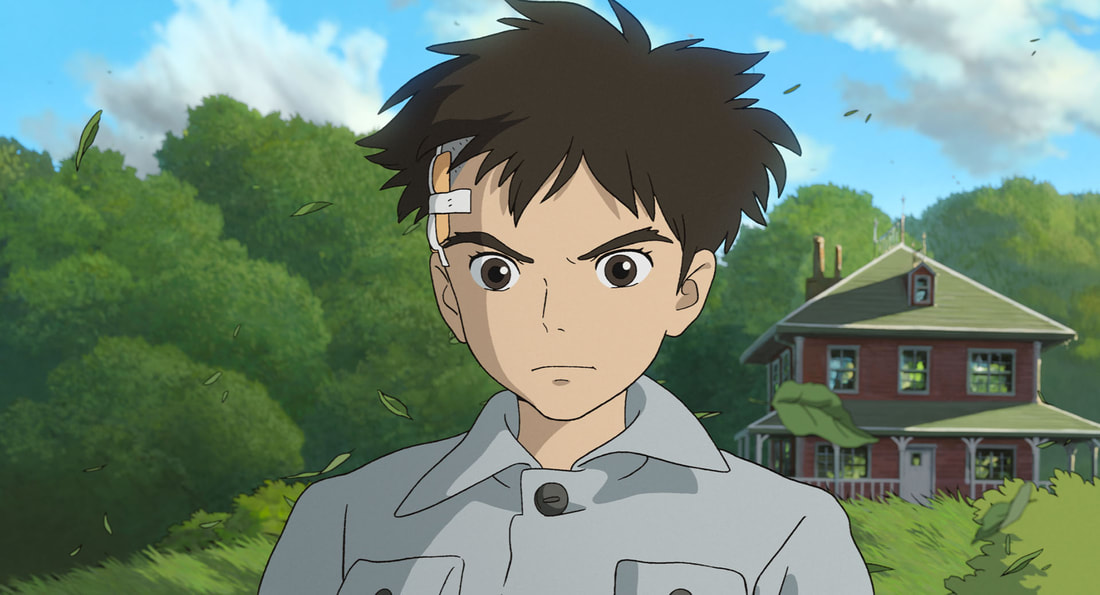

Evan D.Grief has long been one of the most well trodden roads traversed by filmmakers. Cinema loves to look at broken people piecing themselves back together or filling in some loss like the final piece of a healing jigsaw puzzle. Many of the great characters of film history are wounded birds desperate to fly again. Forged in the fire of loss and pain, great heroes emerge stronger for what they have endured. Hayao Miyazaki’s filmography has explored the deep thematic well of grief, but has often opted to mine deeper. My Neighbor Totoro is a film that leaves the pain on the periphery and focuses on the ability of children to shield themselves from forces that might hurt them. With The Boy and the Heron, Studio Ghibli’s great auteur asks not how a broken child might repair himself, but whether a shattered life is worth resurrecting at all. Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki) suffers the most traumatic loss imaginable for a young boy, losing his mother in a hospital fire near the end of the Second World War. In a stunning bit of animation, Mahito runs into the towering inferno desperate to save his mother to no avail. Wasting no time, the boy’s enterprising father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) quickly begins a romance with Natsuko (Ko Shibasaki) the sister of his deceased wife and moves the family to her estate. Already battered by the loss of a mother, Mahito is uprooted and forced to a strange new home, ridiculed by classmates in his new school and deeply resentful of his new family. Overnight his life has imploded, leaving only jagged shards to serve as a prickly defense.

For much of the first half, The Boy and the Heron is a surprisingly grounded film for the man whose most acclaimed work is Spirited Away. This is still a Miyazaki picture and things escalate quickly as a Gray Heron (Masaki Suda) begins to taunt Mahito and attempts to lure the boy to a mysterious tower in the woods with claims that his mother is still alive. Mahito is understandably skeptical of such claims, but when his aunt goes missing he seeks her out in the depths of the tower and is transported to a fantasy world beyond time and space. At this point The Boy and the Heron builds up a beautifully rendered, fantastically imagined and deeply metaphorical realm. For me, Ghibli films have always connected more in their simplicity and childlike wonder, faltering when the mystical beings become more abstract and sinister. This time we get a little bit of each, grounding the stakes of the journey before unleashing a rich allegory populated by colorful and lively creatures. A blend of Miyazaki’s styles that offers something for everyone. What Miyazaki inflicts upon Mahito is agonizing and it is not immediately clear if it is more than his protagonist can handle. As if it is the only way to make his suffering meaningful, Mahito traverses a world of fire goddesses and parakeet soldiers, singularly driven by a mission to save Natsuko. Eventually he comes across his great uncle and asked to take over control of this world and maintain it by stacking a collection of misshapen blocks every three days. Build it well and it can be a place of beauty and wonder, but build it carelessly and it might just descend into chaos. It is easy to recognize this handoff, from a seasoned world builder to his progeny, as Miyazaki passing along the acclaimed studio he helped to build and has maintained over his life to the next generation. He has said The Boy and the Heron will be his final film, a claim he has made before, making this read a strong fit. More interesting to me is what this allegory means to Mahito as a character and what it represents to those still consumed by the flames of grief. The broken pieces of Mahito’s old life similarly do not fit snuggly together, rebuilding a life will require him to exert continuous effort to carry on. Until now, he has not had any interest in rebuilding. He has the building blocks but it is up to him what kind of life he will construct with them. Released under the apt title How Do You Live in Japan, The Boy and the Heron relentlessly examines the effort it takes to manufacture existence under the pressure of loss and the ongoing project of maintaining it. We do not know if Mahito can keep going on forever but he does try for the sake of his makeshift family. If this is truly a swan song for Hayao Miyazaki it is a stunningly beautiful one. Bleak as it is at times, hope for a better future and a better world is animated with the delicacy of a teetering block tower. Every frame is shown more immense care than the totality of Disney’s tentpole animation release just weeks ago. Joe Hisaishi’s wistful, longing score haunts the background of Mahito’s journey. In an industry dominated by 3D models and computer generation, the artwork on display is a gripping display of what we’ve all lost from the virtual abandonment of hand drawn animation in the United States. How we structure our lives and personal worlds matter tremendously to the people around us. Grief is a constant in the world, not a variable. For as bleak as Mahito’s experience is in The Boy and the Heron, his lesson is that we go on only by choosing the difficult task of picking up our pieces and putting them back together in an additive fashion. What a tremendous loss we will all suffer as Miyazaki says goodbye to the medium he has bent to his whim. With hope Studio Ghibli will be able to pick up the pieces and carry on that legacy. 9/10

Comments

|

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|